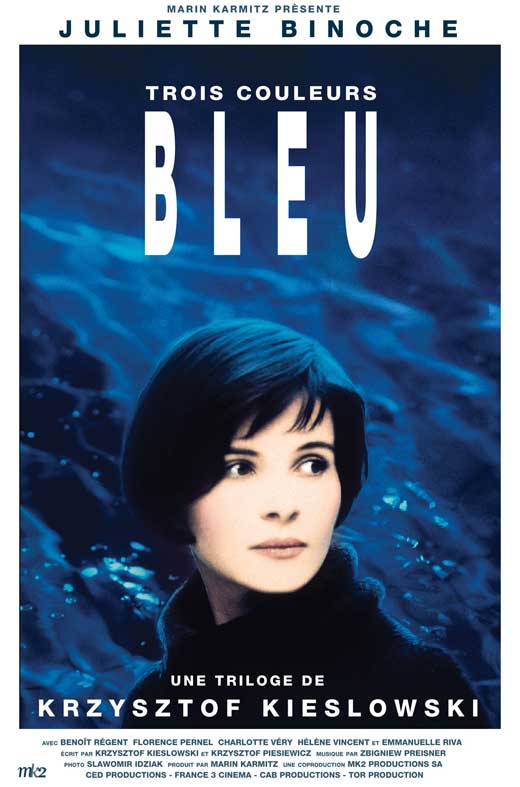

Trois couleurs: Bleu

3 STARS

General Information:

Information below is taken from the following link: http://www.imdb.co.uk/title/tt0108394/

15 98 min – Drama | Music | Mystery – 15 October 1993 (UK)

Director

Writer

Krzysztof Kieslowski; Krzysztof Piesiewicz;

Stars

Juliette Binoche; Zbigniew Zamachowski; Julie Delpy

Plot:

First film in Krzystof Kieslowski’s Three Colours Trilogy.

Julie and her family have a car-crash. She wakes up in hospital to discover that her husband and son have died.

Review:

Sometimes I just feel utterly rejected by art-films where nothing particularly happens, whilst everyone else is ‘deeply’, ‘profoundly’ and ‘mesmerizingly’ moved by them – such is the case with Three Colours Blue. Here we have a film perhaps influenced by Italian Neo-Realism: all of the events after the car-crash happen through chance, are random and feel slightly disconnected – like life. There is no sense – like in a Classical Hollywood Narrative – of one event leading to the next, leading to the next, then leading to an explosion and a sex scene shot with orangey mood-lighting. This is not necessarily a bad thing, and one of the reasons why I liked Blue very much.

Following the car-crash, everything is mundane and horrifically normal. There are frequent amounts of moments where there are long unsettling silences. When Julie does talk, it is only ever in small sentences, sometimes inaudible mumbles. Juliette Binoche, who plays Julie is deeply and profoundly mesmirizing in this film – and I am not being sarcastic. She does that rare thing, when she is no longer ‘a character’, but a real person. She can stare into the camera, not moving any muscle on her face and seem totally real; she acts with her eyes rather than her face. In fact, she hardly ever acts in this film because we can never see her ‘act’, rather she is being this deeply complex character. Nothing in her performance ever feels ‘forced’. This is a difficult thing to do. Most actors given the chance, would plunge straight in and start externalising all of these emotions, Binoche does the opposite and internalises them – a smart move and I commend her for it.

After the car-crash, Julie drifts in and out of coffee-shops, street-corners, houses and gardens, and occasionally meets someone, converses with them, and will never talk to them again in the film. Perhaps she does, but only briefly. They are insignificant to the plot in the same way that they are too her life. The film really concerns her and is about her reactions, how her views on the world change, and how she expresses this by interacting with objects and other people. It is an interesting and excellent case study. I cried three times in the opening 45 minutes.

The director, Krzystof Kieslowski is a director who understands the relevance of actors in films. Too often is it the case, that I am never moved by a performance – not necessarily because it is a bad one, but because the director shoots it in such a way, that it is never in full focus, as if the actors are just another set of cogs and wheels in the whole mechanics of the film. Kieslowski dispenses with this despicable construct, and he incorporates as many close-ups on Binoche’s face as possible to ensure that the viewer is engaged with what is occurring in her thoughts. There is one striking moment, when Binoche’s character wakes up in hospital, after the car-crash, at the beginning of the film. It is an extreme-close-up of her eye. Never has the phrase ‘the eyes are the windows to the soul’ been exploited as much as this since that horrifically unsettling shot in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Following this, she leaves the ward, breaks a window as a distraction and then sneaks into the medical cupboard. She finds a box of pills, unloads multiple pills into her hand, and puts them in her mouth. But she cannot swallow. This moment feels utterly real as opposed to melodramatic – the camera focuses completely on the reactions of Julie’s character, to the extent that we can almost attempt to guess at why she did not kill herself.

Julie tries to recover from what has happened in the most unexpected of ways. She calls an old friend over, they have sex. This, however, never feels out of place. It feels perfectly normal. The scene isn’t meant to shock, but rather to make a point about Julie’s character. She doesn’t enjoy sex, she has lost all feeling.

She abandons her mansion and goes to a flat in town so that nobody can find her. She wants to completely reinvent her life. However, she can’t erase the thoughts from her head. There is a moment when she is in a swimming pool, and suddenly a group of children enter – she puts her head against the sides of the pool, and the thoughts of her dead child come rushing back.

I have said all of this praise, and you would have expected that this film would have been five stars. But, I find that the film never particularly went anywhere. Not necessarily in plot, but in character. I have nothing wrong with films where its plot(s) meander into a black hole. I like Slacker. But Slacker doesn’t have such an interesting central character. Julie is so mysterious and quite clearly complex. We want to know her more and no more about her, but Kieslowski puts a hand against our shoulder so we can’t get closer towards her. It felt more of an annoyance that we are presented with such a unique and well-portrayed character, but are prevented to know more about her. We are presented with what she shows the world as opposed to what she thinks. Perhaps this is the point, but if so it’s damned irritating.

After 45 minutes, the films tone never changed and it stayed constant: all of these shots of this ambiguous character living normally, but knowing that she is unlike anybody else. The film plodded on like this constantly and constantly. I wasn’t bored, but rather I became progressively uninterested. I knew that the film would hold onto itself and never let me get closer to the inner-workings of this character’s deeply troubled mind. If anything, the fact that I knew that the film would stay the same, was more of an inconvenience.

Verdict:

Contains one of the most fascinating characters ever in cinema. Julie is up there with Lisbeth Salander in The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo and Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver. Yet, we’re never allowed to get inside her mind. Sometimes, the mystery of a character’s thoughts and personality is an advantage, but here, I don’t think it worked, and I really wanted to know and understand her more.